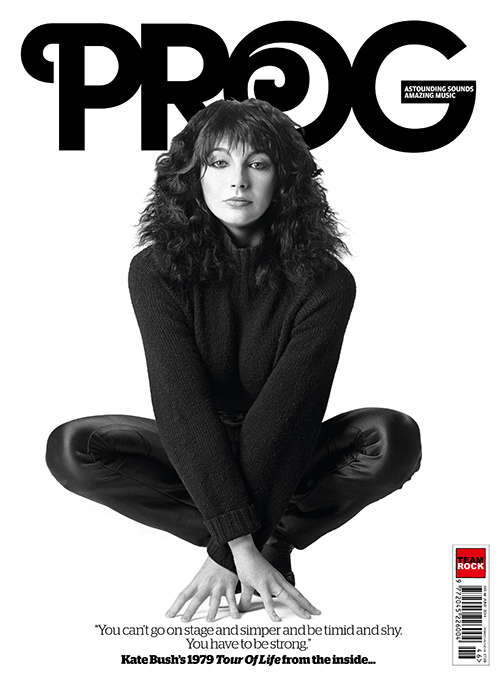

Kate Bush’s 1979 road trip, The Tour Of Life, has become the stuff of myth and legend – especially since it’s the only time in her career she ever toured. In 2014, ahead of her return to the stage with Before The Dawn, Prog looked back at The Tour Of Life.

Kate Bush has long cornered the market in reclusive, media-averse mystique, but it wasn’t always that way. On April 3, 1979, early evening news show Nationwide dedicated a show to the 20-year-old singer.

The event on which the 25-minute special was hung was the opening night of her first – and to date only – tour. “Most live artists make their mistakes either in private or in front of a very small audience,” intoned the moustachioed reporter. “Tonight, Kate Bush starts at the top, in front of several thousand. She can’t afford to fail.”

But then Bush was big news. Her star had been arcing across the firmament ever since she first appeared on Top Of The Pops just over a year earlier. That memorable performance, playing her first single, Wuthering Heights, had introduced her as an utterly new and fresh talent. There had been an instant clamour for her to play live, though it would be 14 months before she did.

Looking at Nationwide from the vantage point of 2014, it’s amazing how much unguarded access she granted the filmmakers over a six-month build-up. Footage of early production meetings where people are crammed onto chairs and sofas in a tiny dressing room is followed by a clip of a leotard-and-leggings-clad Bush being worked hard by choreographer Anthony Van Laast during three initial weeks of “gruelling exertion” just to prepare her for several weeks of even more intense choreography.

Remarkably, the camera was allowed into Wood Wharf Studio in Greenwich, south London, where the singer was drilling her eight-piece band through Kite and Wow. Here, it’s possible to get a real sense of the pub gigs she’d started out playing just a couple of years before. “I think the main reason they listen to me is because I’m paying their wages,” she says of the rest of the band, her girlish, sing-song voice cut with chewy south London vocals.

Towards the end, after a brief post-gig chat with an exhausted but exhilarated Bush at the Liverpool Empire, the camera cuts back to an earlier interview. Sitting with her back to a studio mixing desk, she puts a ‘posh’ interview voice on as she answers a string of questions.

At one point, the off-screen interviewer asks, given that she’s achieved so much so swiftly, what has she got left to achieve? “Everything – I haven’t really begun yet,” she says, offering a glimpse of the maturity and self-awareness that have always driven her. “I’ve begun on one level, but that’s all gone now, so you begin again.”

She would “begin again” many times over during the ensuing years, but never would she do it onstage. She didn’t retire entirely from live performances – there would be the odd one-off here and there throughout the 80s – but never again would Kate Bush put herself through such an exhilarating, groundbreaking, draining experience as her 1979 tour.

I feel I owe people a chance to see me in the flesh. It’s the only opportunity they have without media obstruction

Kate Bush

When Bush announced 15 dates at London’s Hammersmith Apollo in 2014 (a figure since bumped up to 22 dates) under the banner Before The Dawn, the reaction was shock and awe. Shock that she was finally following up that original tour, a promise she’d made many times but all but her most optimistic fans had long given up hope on her ever keeping. And awe at the prospect of what a woman who broke so much ground could deliver with 35 years of artistic and technological advancements at her disposal.

But there was also a question of just how she could follow up the original spectacle, retrospectively dubbed The Tour Of Life. 35 years on, that extravaganza had grown to almost mythical status – a strange state of affairs given that it was witnessed by more than 100,000 people at the time.

Footage of an hour or so of the show is available on YouTube, highlighting a performance that bridged the worlds of music, dance, theatre and art. But there’s even more footage that has never been made public – including that of the magician Simon Drake, who played seven different characters during the show.

But in many other respects, the tour was utterly grounded in reality. The singer spent six months beforehand working herself to the bone as she attempted to forge a brand new model of what a live show could be, then another two months doing the same as she took it around Britain and Europe. And it was hit by tragedy when lighting engineer Bill Duffield was killed in an accident after a warm-up show, his death almost bringing the whole juggernaut to a halt before it had even started.

But all that was in the future when the idea for the tour was conceived. Ironically, Bush herself was the first to admit that there was no need for her to do it. “There’s no pressure,” she said in 1979. “But I do feel that I owe people a chance to see me in the flesh. It’s the only opportunity they have without media obstruction.”

“Kate was never at ease in the public eye,” says Brian Southall, who worked in artist development at Bush’s label, EMI, and had collaborated with the singer since she was signed. “Whether that was performing on Top Of The Pops or doing interviews. She was very reserved, very wary, I think by nature shy. So this spotlight on her was new.”

The story was that you put singles out, you put albums out, you went on Top Of The Pops, you toured. She wouldn’t do the conventional thing

Brian Southall

The singer was fully aware that anything she did would have to raise the bar on everything that came before. But even then, she was trying to manage expectations – not least her own. “If you look at it, it’s my reputation,” she said 1979. “And yes, I hope that it’ll be something special.”

EMI were unsure what the show would involve, so the costs were reportedly split between the label and Bush herself. In return, they got an artist who threw everything into her biggest endeavour so far.

“She was very determined about how her music was presented and performed – that was pretty obvious from her first album,” says Southall. “So no one saw any reason to step in and stop it. The rock’n’roll story was that you put singles out, you put albums out, you went on Top Of The Pops, you toured. But she wasn’t prepared to do the conventional thing.”

In fact no one realised just how unconventional it would be – with its choreography, dancers, props, multiple costume changes, poetry and in-house magician, there was no precedent with which it could be compared.

Rehearsals began in late 1978. Bush had already trained with experimental dancer/mime artist Lindsay Kemp, one-time mentor of David Bowie. But this tour would entail a new level of aptitude entirely, and the stamina to simultaneously dance and sing for more than two hours every night.

Dance teacher Anthony Van Laast was brought in from the London School Of Contemporary Dance to choreograph the shows and help hone Bush’s abilities. Van Laast brought with him two protégés, dancers Stewart Avon Arnold and Gary Hurst. Van Laast put the singer through the equivalent of boot camp at The Place studio in Euston, working with her for two hours each morning. Bush’s own input was crucial to the developing routines.

You have to make things more obvious so people can hear them,. Maybe make them faster

Kate Bush

“Kate knew what she wanted – she had very specific ideas,” says Stewart Avon Arnold. “What she wanted was in her head, and she wanted people around her who could help her put it into movement. She had so many hats on at that point – artistic, creative, musical.”

If the mornings were for the dance aspect of the slowly coalescing show, then the afternoons were for the music. As soon as she was done with Van Laast, Bush would make the eight mile journey to Wood Wharf Studio in Greenwich, south London, where she would meet up with a band that included Del Palmer, guitarists Brian Bath and Alan Murphy and her multi-instrumentalist brother, Paddy Bush. Also present was her other brother, John Carder Bush, who would perform poetry (and whose wife would provide vegetarian food for the tour). It was hard work for everyone involved and as the show neared, Bush would work 14 hours a day, six days a week.

“You have to make things more obvious so people can hear them,” she said of the live interpretation of her songs. “Maybe make them faster.”

While Bush was utterly in command, sometimes necessity was the mother of invention. With the singer literally throwing her whole body into her performance, holding a traditional mic would be difficult. So a mic that could be worn around the head was devised.

“I wanted to be able to move around, dance and use my hands,” she said. “The sound engineer came up with the idea of adapting a coat hanger. He opened it out and put it into the shape, so that was the prototype.”

In early spring 1979, the various creative wings finally came together at Shepperton Studios. There was the odd stumbling block. Del Palmer, Bush’s bassist and boyfriend, was less than impressed with some aspects of the choreography when he first saw it.

“In those days, dance wasn’t as popular as it is now, and I don’t think Del was clear on what we were doing,” says Stewart Avon Arnold. “There was a bit where we picked Kate up. I remember him going, ‘What they hell are they doing to Kate! They’re holding her between the legs!’”

In late March, a week before the tour was due to start, the whole production moved to the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park, north London, for dress rehearsals. Like everything over the past six months, the whole endeavour was undertaken in secrecy.

If money was her concern, she’d have been making albums every year rather than every 10 years… creativity was all-important

Brian Southall

“It’s like a present that shouldn’t be unwrapped until everyone is there,” reasoned the singer. “It’s like hearing about a film. Everybody tells you it’s amazing – and you could end up disappointed. You shouldn’t get people’s expectations up like that.”

By the time the tour was due to start on April 3 in Liverpool, everyone drilled to within an inch of their existence. If Bush was nervous, she wasn’t letting on.

“There was no suggestion that Kate was scared about going on the road,” says Brian Southall. “I certainly never got a sense that she was nervous about the financial aspect of it. If money was her concern, she’d have been out making albums every year rather than every 10 years. It’s not something that crossed her mind. The creativity was all-important.”

Still, to iron out any potential last-minute problems, a low-key warm up show had been arranged at the Poole Arts Centre in Dorset. It was there that tragedy struck.

Lighting director Bill Duffield was an integral part of the show. A 21-year-old boy wonder who had worked with Peter Gabriel and Steve Harley, he shared the same forward-thinking mindset as Bush herself.

The circumstances of what happened in Poole remain unclear. Some reports said that Duffield fell from the lighting rig while helping to clear the stage away following the show, others said that he fell 20 feet through a hole in the stage. Either way, Duffield sustained serious injuries that would result in his death a week later.

“People were concerned for his wellbeing,” says Brian Southall, who met up with the Bush entourage in Liverpool the following night. “They were wondering how he was and if and when he would recover. Sadly he didn’t. I think the real shock came when his death was announced.”

24 hours later, with the Nationwide TV cameras posted outside the Liverpool Empire, Kate Bush’s first tour got properly underway under a cloud – albeit one the public weren’t aware of.

If the build up had been intense, then the show itself was a magnificent release. Theatrically divided into three acts, the 24-song set featured tracks from her first two albums, The Kick Inside and Lionheart, plus two as-yet-unheard tracks, Egypt and Violin.

When I perform it just takes over. It’s like suddenly feeling that you’ve leapt into another structure, almost like another person

Kate Bush

But that was where any similarity with a standard rock show began and ended. On an ever-shifting stage of which only a central ramp was the sole constant physical factor, Bush was a human conductor’s baton leading the entire show. As the scenery shifted through the opening Moving, Room For The Life and Them Heavy People, so did the costumes – and the atmosphere.

“I saw our show as not just people on stage playing the music, but as a complete experience,” she later explained. “A lot of people would say ‘Pooah!’ but for me that’s what it was. Like a play.”

Indeed it was – or perhaps several plays in one. On Egypt, she emerged dressed as a seductive Cleopatra. On Strange Phenomena, she was a magician in top hat and tails, dancing with a pair of spacemen. Former single Hammer Horror replicated the video, with a black-clad Bush dancing with a sinister, black-masked figure behind her, while Oh England My Lionheart cast her as a World War II pilot.

Like every actor, she was surrounded by a cast of strong supporting characters. As well as dancers Stewart Avon Arnold and Gary Hurst, several songs featured Drake, who performed his signature ‘floating cane’ trick during L’Amour Looks Something Like You. And then there was John Carder Bush reciting his poetry before The Kick Inside, Symphony In Blue (fused with elements of experimental composer Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie 1) and the inevitable encore, Wuthering Heights.

But at the heart of it all was Bush, whirling and waving, reaching for the sky one moment, swooping to the floor the next. Occasionally she looked like she was concentrating on what was coming next. More often, she looked lost in the moment.

“When I perform, that’s just something that happens in me,” she later said. “It just takes over, you know. It’s like suddenly feeling that you’ve leapt into another structure, almost like another person, and you just do it.”

Brian Southall was in the audience at the Liverpool Empire. Despite the fact he worked for EMI, he had no idea what to expect. “You just sat in the audience and went, ‘Wow’. It was extraordinary. Bands didn’t take a dancer onstage, they didn’t take a magician onstage, even Queen at their most lavish or Floyd at their most extravangant. They might have used tricks and props in videos, but not other people onstage.

“That was the most interesting thing about it – her handing it over to other people, who became the focus of attention. That’s something that never bothered Kate – that ‘I will be onstage all the time and you will only see me.’ It was like a concept album, except it was a concept show.”

Like most support acts, she was going to get half an hour, no dancers and no magicians… she wasn’t prepared to do that

Brian Southall

Two and a quarter hours later, this ‘concept show’ was done and the real world intruded once again. If there was any sense of celebration afterwards, then the main attraction was keeping it to herself. “I remember sitting in the bar after the show at Liverpool and Kate wasn’t there. She was with Del,” says Southall. “She wasn’t an extrovert offstage. There were two people. There was that person you saw onstage, in that extraordinary performance, and then offstage there was this fairly shy, reserved person.”

Her reluctance to indulge in the usual rock’n’roll behaviour was both characteristic and understandable. It was a draining performance, night after night as the tour continued around Britain and then into Europe. It was hard work for everyone involved.

“We went out, but not exceptionally,” says Stewart Avon Arnold. “We weren’t out raving until seven o’clock in the morning on heroin. There’s no way we could have done the show the next day.”

They occasionally found time to let their hair down. The Sunday Mail reported that certain members of the touring party indulged in a water-and-pillow fight at a hotel in Glasgow, causing a reported £1,000 damage. EMI allegedly agreed to foot the bill, though they stressed that the singer wasn’t present during this PG-rated display of on-the-road carnage.

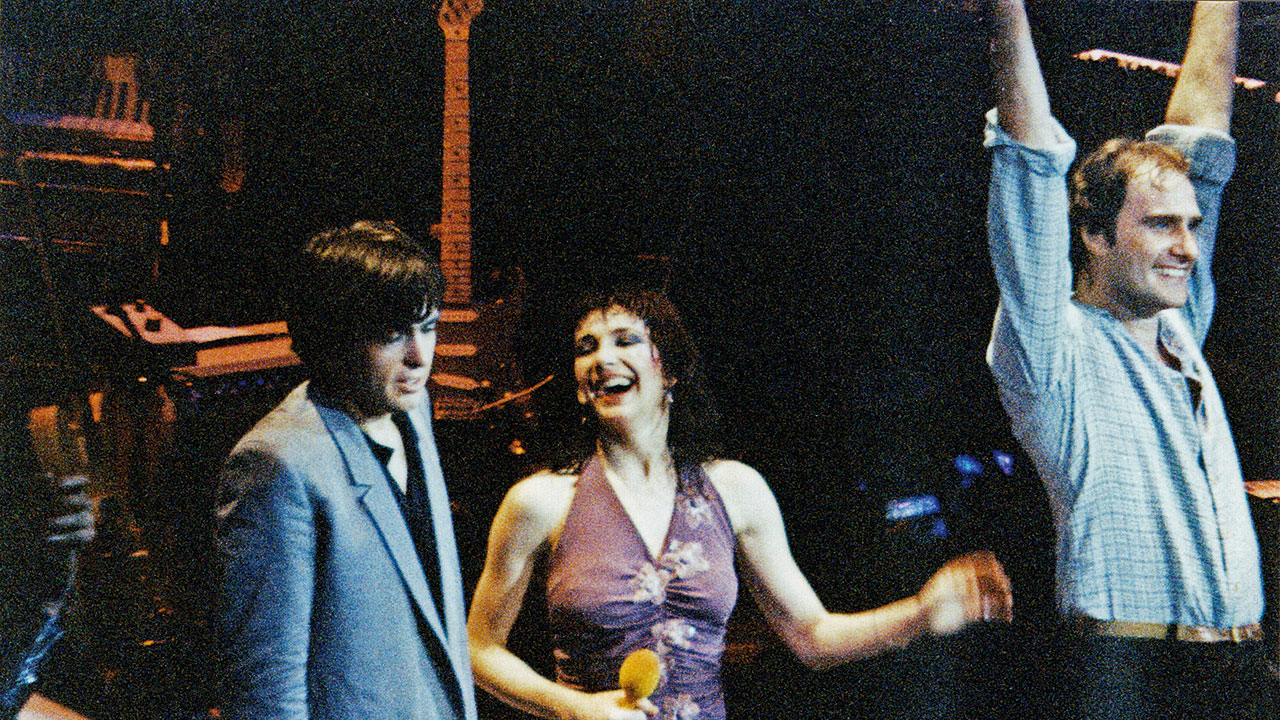

After 10 shows in mainland Europe, the tour returned to London for three climactic dates at the Hammersmith Odeon between May 12 and 14. The second of these shows was arranged as tribute to the late Bill Duffield. Bush and her band were joined onstage by Peter Gabriel and Steve Harley. The pair tackled various Bush songs (Them Heavy People, a renamed The Woman With the Child In Her Eyes) and played their own songs (Gabriel’s Here Comes The Flood and I Don’t Remember, Harley’s Best Years Of Our Lives and Come Up And See Me), before everyone came onstage for a cover of The Beatles’ Let It Be.

“Kate asked us all to come and sing with Peter and Steve,” says Avon Arnold. “We were onstage, singing chorus with these two icons. And I’m not a singer. It was an emotional night.”

48 hours later, the tour was over. And so was Kate Bush’s career as a live artist – at least for another 35 years.

She was the first one in this country to merge creative rock music with creative dance

Stewart Avon Arnold

Kate Bush hasn’t truly explained why she never took to the road again after that very first tour. Various theories have been posited – a fear of flying, the psychic damage inflicted by the death of Duffield, the sheer effort of will and vast reservoir of energy that it took to get what was in her head onto the stage. The latter seems most likely, though it could just as easily be a combination of all three. Or it could be none of them.

“I need five months to prepare a show and build up my strength for it, and in those five months I can’t be writing new songs and I can’t be promoting the album,” she once said, the closest approximation to a reason she has ever offered. “The problem is time… and money.”

Not that there wasn’t a call for it, especially overseas. America was one of the few countries where she didn’t sell records, and the idea was floated that she play a show at New York’s prestigious Radio City Music Hall so that her US label, Capitol, could bring all the important media and retail contacts to the show to see what the fuss was about. “She’s not a great flier,” says Southall. “And she wouldn’t do it.”

Even more tantalising was an offer to support Fleetwood Mac in the US in late ’79. A high-profile slot opening for one of the most successful bands in the world would was an open goal for most artists. But Bush wasn’t most artists.

“Like most support acts, she was going to get half an hour, no dancers and no magicians, so just going up there with four musicians and banging out a couple of hits,” says Brian Southall. “And she wasn’t prepared to do that.”

Not that she has ever ruled it out. In fact, in all of the increasingly infrequent interviews she has given since then, she’s been asked when she would next tour. The answer has always been a charmingly vague tease that, sure, it could happen if the circumstances were right. She once floated the idea that she would write

a concept album specifically to base a stage show around (it never materialised), while at one point she was rumoured to be working with Muppet creator Jim Henson’s Creature Workshop on a new idea, even announcing in 1990 that she would be playing live the following year (that never materialised either).

But now, out of the blue, she’s finally delivered on that promise (though, tellingly, it’s for a residency rather than a tour). “She’s only playing one venue,” says Southall. “That means she can nest without the hassle of taking it all on the road for weeks on end.”

What exactly her belated live return holds in store for her fans isn’t clear. “I don’t know whether she’ll refer back to the original show in any way,” says Southall. “Will there be dancers, will there be magicians, will there be dancing elephants? I think she feels comfortable with more people onstage with her. I think the idea of her sitting down at a piano and playing an hour and a half of Kate Bush songs would terrify the life out of her. The idea of having people around who she is comfortable with and finds some support from, whether that’s Dave Gilmour turning up or whoever.”

The only thing that’s certain is that it won’t be a by-the-numbers live show.

“She’s an innovator,” says Avon Arnold. “She did things that had never been done before. She was the first one in this country to merge creative rock music with creative dance. She didn’t have a genre. She had a mentality.”